BIOGRAPHY

One of the few native Southerners to study at Black Mountain College, Sewell Sillman was born in Savannah, Georgia. He attended high school in Atlanta before enlisting in the United States Army Air Force Reserve in 1942. That same year, he enrolled in evening engineering classes at the Georgia Institute of Technology; his military training included studies at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Assigned to the European theater during World War II, Sillman was wounded in the Battle of the Bulge. After his discharge, Sillman returned to Georgia Tech in early 1946, but bristled at the university’s constrictive environment, prompting one instructor to label him a “misfit.”

Sillman’s affiliation with Black Mountain College and Josef Albers began in January 1948. His intention was to study architecture, but he became disenchanted during the summer session, when Buckminster Fuller oversaw the unsuccessful construction of the first geodesic dome. Stimulated instead by Albers’ design and drawing courses as well as Pete Jennerjahn’s printing classes, Sillman shifted his focus. He remained at Black Mountain through the following summer and later revealed how the experience “gave me a chance to get rid of absolutely every standard that I had grown up with. . . . It was like a snake that loses its skin. . . . What was left was someone who had absolutely no idea in the world what to do. . . . It was marvelous.”

In 1950, Sillman entered the bachelor of fine arts program at Yale University where Albers had become the director of the design department. Already well versed in art studio practices, Sillman obtained his degree quickly and went on to pursue a MFA. He served as a teaching assistant to Albers, and in 1954 became a regular faculty member, a position he held until 1966. Sillman returned to Black Mountain for the summer of 1952, but found the place changed and dominated by faculty proponents of Abstract Expressionism such as Franz Kline and Jack Tworkov. “When Albers left it was just so empty,” he recalled.

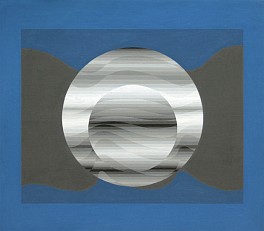

In his own work, Sillman continued to examine basic design and drawing concerns, such as the relationships of colors and shapes, and the use of line, investigations that evolved from his teaching regimen. His oil paintings are formal minimalist exercises with non-primary hues applied with a palette knife to create bold geometric compositions. In contrast, his series of “wave drawings,” artfully filled with curving lines, are organic and reminiscent of forms in nature.

Sillman organized a 1956 exhibition of Albers’ work for Yale’s new art gallery, including in the companion catalogue two original screenprints from his mentor’s Homage to the Square series. The project fostered a collaboration between Sillman, and fellow Yale faculty member and graphic designer, Norman Ives. In 1962, they established the art publishing firm of Ives-Sillman, which one year later issued Interaction of Color—1800 portfolios of eighty screenprints by Albers which became a seminal thesis on color theory. Ives-Sillman went on to produce portfolios and high quality prints for other artists, including Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, Roy Lichtenstein, and Walker Evans.

Described as a quiet man who valued his privacy, Sillman was also a dedicated and demanding educator. Between 1963 and 1965, he taught at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, and after his departure from Yale in 1966, held positions at the Rhode Island School of Design, the State University of New York at Purchase, Ohio State University, and the University of Pennsylvania. Sillman’s work was widely exhibited during his lifetime and is represented in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art and Whitney Museum of American Art.

(From the Johnson Collection)